DEBORAH TURBEVILLE’S bathhouse pictures in the May 1975 issue of Vogue changed my world. Her women looked dissolute, depressed, louche, lonely, self-involved—far more in sync with my own inner life than the fashion photos I’d seen in Seventeen and Mademoiselle. They were shot in restrooms and public showers, places I’d begun to explore in my own photographs. Around the same time, I also discovered Helmut Newton, Chris von Wangenheim, Sarah Moon, and Guy Bourdin. Bloomingdale’s had commissioned Bourdin to shoot the now-infamous Sighs and Whispers lingerie catalogue of 1976. Rumor was he’d had total artistic control and Bloomingdale’s didn’t see any of the final images until he’d returned to Paris. The mysterious pictures, with their saturated nocturnal palette, felt both homoerotic and like an overage pajama party. They looked more like “art” photography than fashion photography, with none of the static, contrived formality of early studio photographs or the bounce associated with post–World War II fashion pictures. The collective work of all these photographers lulled me into thinking I was meant to be shooting fashion, not making art.

As for the violence directed toward women in some of the photographs—there were definitely two sides to the discussion of BDSM in second-wave feminism. At the time, my close friend Jimmy DeSana was documenting the underground s/m scene in 1970s gay culture, so the heterosexual version of women and bondage in fashion did not seem threatening to me. Fashion murder mysteries and sadomasochistic fictions seemed more about costume and fantasy play than about harming or objectifying women.

Then everything got big in the ’80s: big hair, shoulder pads, intense makeup, drama. Photographers began to craft editorial-like ad campaigns borrowing heavily from art, documentary, and portrait photography, and these aesthetics suddenly spilled into one another. Fashion photography became extremely lucrative as photographers and models reached superstar status. Bruce Weber and Denis Piel were making splashy print ads for such iconic perfumes as Poison, Obsession, and Opium. Jovan Musk sponsored a Rolling Stones tour and had ads directed by Adrian Lyne. TV spots were like mini movies, with sexual innuendo, slow motion, orgies, and stylistic nods to everything from Raiders of the Lost Ark to Spartacus. Glenn O’Brien wrote and directed a number of them, collaborating with Steven Meisel, Richard Avedon, and Patrick Demarchelier. By the early ’90s, David Lynch had directed an Armani Giò TV spot and Jean-Paul Goude had made my favorite ad, for Chanel’s Égoïste cologne. The commercial starts out in black-and-white with dozens of fashion models in evening gowns standing on the balconies of a rococo hotel, shouting lines in French from a poem about egoism. Then the scene turns to color while the women throw the doors open, scream “Égoïste!” and slam them again. The ad seemed to be loosely based on one of my favorite fashion photos, the 1960 Girls in the Windows by Ormond Gigli, which shows forty-three women in evening gowns standing in the windows of a row of soon-to-be-demolished brownstones on East Fifty-Eighth Street in Manhattan.

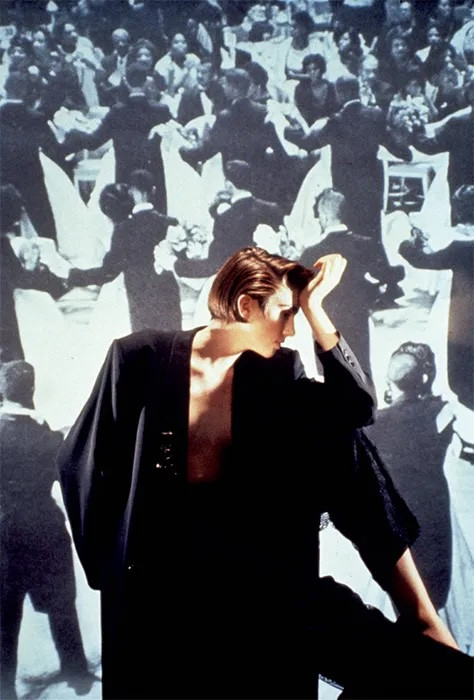

In 1984, the Brooklyn Academy of Music commissioned me to shoot some fashion pictures for their Next Wave Festival catalogue. I used the same rear-screen-projected images I’d used in my “Tourism” pictures, 1983–84. The models stood in front of an eight-by-ten-foot screen; behind it, a Kodak carousel projector automatically changed background slides from a huge picture archive I was amassing. So my “Fake Fashion” series, 1983–85, came out of a moment when I wasn’t getting any fashion work. I wanted to keep shooting real people rather than dolls and mannequins, so I devised my own “pretend” fashion shoots. I bought the clothes at shops on Fourteenth Street—100 percent polyester skirts with knife pleats and ruffled blouses that photographed like molded plastic outfits. At the same time, I was creating a shadow of a fashion photograph that wasn’t selling anything in particular. These were fashion photos without context, client, merchandise, editor, or—ultimately—fashion photographer. It was sheer mimicry, with nothing but a desire on my part to understand the construction of the fashion message.

Fashion photography has borrowed from visual art and vice versa—the differences can seem indistinguishable. I have to dig deeper to find interesting fashion stories now, but that has as much to do with the changing terrain of the magazine world as it does with the kind of work that’s out there. When I was a teenager I wanted to be a fashion illustrator. That was a job! Most people can’t even remember how much gorgeous illustration existed in magazines and newspapers.

I tend to keep separate the pictures I think of as “assignments” from pictures I think of as “my work.” I’ve rarely shown what I consider to be my “commercial” work in a gallery context, though I think many of those photos are stronger pictures on a purely visual level. Looking back through notebooks of commercial photos from the ’80s through the present, I would say I tend to think through assignments by revisiting themes from earlier work rather than mining current ideas. I shot an underwater makeup story for Mademoiselle (July, 1983) that was commissioned by Condé Nast’s editorial director Alexander Liberman after he saw my 1980–81 “Water Ballet” series. For one of my favorite stories, “The Perfect Companion” in the New York Times Magazine in 1994, I recycled my ventriloquist dummies (from the series “Café of the Inner Mind” and “The Music of Regret” that same year), and twinned them with fashion designers.

When I’m considering an assignment, I try to find the visual language to solve the problem. For a recent shoot, New York magazine sent over hundreds of spring accessories: shoes, bags, and jewelry. I picked about fifty to photograph in the studio. We had the pictures blown up and made into 2-D placards that dancers from the Broadway musical Chicago, wearing black leotards and balaclavas, held in front of them, so that the shoes and purses were at human scale. Two choreographers on set devised dances on the spot. I shot it as much like a classic Broadway revue as I could. I particularly liked working with a jib arm, which for me was like a drone flying around the stage, capturing the movement. The tricky part was shooting a film and an eighteen-page print story on the same day, as those are such different mental spaces for me.

I’ve lived through many trends. These days, the changes are happening fast and furious—they can’t be quantified. I see some of the best fashion images on Instagram. Wes Gordon just launched his fall 2016 collection on that platform, with nine video vignettes. And apparently J. W. Anderson streamed his runway show on Grindr! Clearly more people can see it online than could sit at a traditional, live, six-minute fashion show. I think one is more likely to see less mainstream fare in magazines that publish quarterly, like Purple, 10, Bullett, V, Love, Wonderland, The Gentlewoman, and Italian Vogue. Otherwise, it’s mostly digital manipulation and action. I was particularly curious about the Lady Gaga and Intel collaboration at the Grammy Awards because I lost track of which were performances and which were ads. Were those ads?

Laurie Simmons is an artist and filmmaker based in New York.